Hello again. Today, let’s take a look at a fundamental part of algorithms – run time. The question that big O notation tries to figure out is ‘How long will it take for something to happen?’ What you’re trying to achieve with big O notation is to get an estimate of how long it will take to accomplish a certain task that the program is trying to do based on how big the data it is handling is. Let’s imagine it this way-

Suppose my friend and I live close to each other.

Suppose one day I find a pirated movie online, and I want to send him the file (sure). Both of our internet connections are really, really slow cause it’s cold and somehow that seems to affect the router. Now, if the movie is really long, like upwards of 90 minutes, sending it over the internet is going to be really slow. Both of us have stuff to do later, so we can’t wait that long. How will we both enjoy pirated movies together then? Obviously we can’t watch it separately.

One solution to this is that I could simply get the movie on a USB, and then start walking along the convenient path apparently made only to connect my house to my friend’s house.

(For anyone confused, the thing in my hand is the USB)

Our houses are about 15 minutes apart if I walk fast. That way, I can get the movie to him in time, and we can both enjoy watching it at the same time (right after I run back to my own house).

Here, we say that the data transfer of the movie file itself takes ‘O(n)’ runtime. Here, this is just saying that the bigger the movie file is, the longer it takes to transfer, which is obvious. If I was just sending my friend a 5 second clip, then it would be done much quicker than if I was sending him a 2 hour movie.

However, the second trick of me running to his house will take ‘O(1)’ or constant runtime. In this case, it doesn’t matter how big the movie is. It’s on a USB, so even if it was a 50 hour documentary, the time it takes for me to grab the USB and run to my friends house will be the same. We can see that if the data file is big enough, it is almost always faster for me to run to my friend instead of waiting to send the file, as the time it takes is constant (not affected by input size).

Now let’s look at this in terms of computer commands. Let’s say we have a line of code like this:

int x = 5 + (12*18);

int y = 12+90001;

System.out.print(x+y);

We say that this is constant runtime again, as this will always take the same amount of time to do. There is no variable input here, as each step is decided in constant time. The actual runtime comes out to O(1) for each step, or 3*O(1) in total. However, we drop any constant multiple as it doesn’t affect the final result, meaning the actual runtime is O(1).

Now, I have another line of code that says:

for x in range (0,n) { System.out.print(x);}

We can’t say that this is constant anymore. Sure, the printing step takes constant time, but how many times is that step carried out? According to the loop, it is carried out ‘n’ times, so the runtime is n*O(1), or O(n). This means that the bigger that the variable ‘n’ gets, the longer it will take to finish this task. Even if I add to the code, say :

for x in range (0,n) { System.out.print(x);}

int y = 12+90001;

System.out.println(y);

This does not affect the runtime, as the final runtime is still (2*O(1)) + O(n). Here, the 2*O(1) is irrelevant, and when calculating runtime, we look at the biggest value to find the final runtime. So the runtime for that block of code is still O(n).

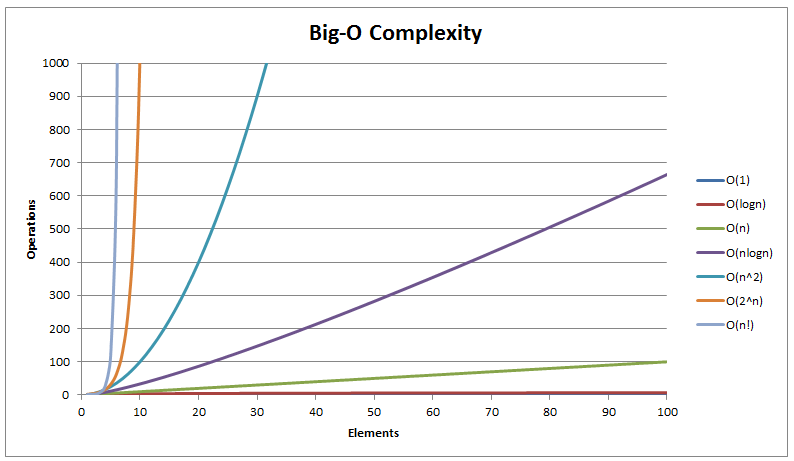

There’s many other versions of runtime algorithms that take different amounts of time to finish, but let’s look at one final one.

If I have this line of code:

for x in range (0,n) { for y in range (o,n) { System.out.print(x*y); }}

Here, the loop is not only carried out once, but once for an ‘n’ number of times. The runtime here is literally O(n) * O(n), or O(n^2). This is slower than both of the previous steps, meaning that this last one gets really, really slow as the input is larger.

Take a look at this video by HackerRank to understand more about big O notation. This is a pretty basic overview. There are other cases to consider, like what if you have an ‘if’ statement where one condition takes constant time, and the other takes quadratic time? Here, you would still say the runtime of the algorithm is quadratic, or O(n^2). While doing big O notation, we are always looking for the worst-case runtime of the code. It doesn’t matter how fast it usually is, it’s about how slow it can be. Also, unlike I said earlier, even if for the official runtime, we consider the biggest value in the runtime as the number, the constants and multiples matter in real life. Just make sure you know that big O gives you a worst case scenario.

If you want a best case, look up ‘big omega notation‘, and if you want an average case, look up ‘big theta notation‘. Runtime just helps you get a feel for how long a task will take. Of course, if you work in CS, you’re job is to make sure that the runtime is as fast as possible, so work on improving it piece by piece. On a side note, don’t run with a USB stick in your hand. It looks suspicious. Next week, we’ll look at another concept, maybe sorting. Until then, good luck.